| Early Life and Career. |

| |

|

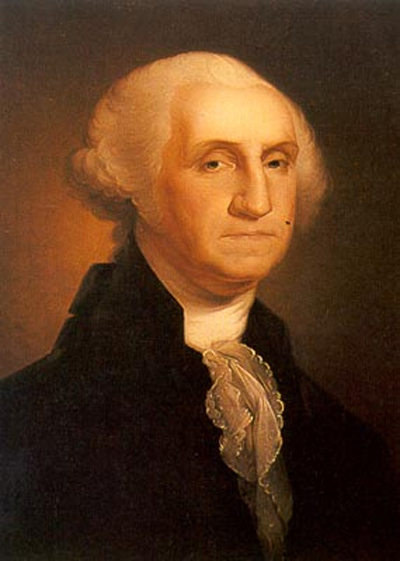

Born in Westmoreland County, Va.,

on Feb. 22, 1732, George Washington was the eldest son of Augustine Washington and his

second wife, Mary Ball Washington, who were prosperous Virginia gentry of English descent.

George spent his early years on the family estate on Pope's Creek along the Potomac River.

His early education included the study of such subjects as mathematics, surveying, the

classics, and "rules of civility." His father died in 1743, and soon thereafter

George went to live with his half brother Lawrence at Mount Vernon, Lawrence's plantation

on the Potomac. Lawrence, who became something of a substitute father for his brother, had

married into the Fairfax family, prominent and influential Virginians who helped launch

George's career. An early ambition to go to sea had been effectively discouraged by

George's mother; instead, he turned to surveying, securing (1748) an appointment to survey

Lord Fairfax's lands in the Shenandoah Valley. He helped lay out the Virginia town of

Belhaven (now Alexandria) in 1749 and was appointed surveyor for Culpeper County. George

accompanied his brother to Barbados in an effort to cure Lawrence of tuberculosis, but

Lawrence died in 1752, soon after the brothers returned. George ultimately inherited the

Mount Vernon estate.

|

| |

|

By 1753 the growing rivalry

between the British and French over control of the Ohio Valley, soon to erupt into the

French and Indian War (1754-63), created new opportunities for the ambitious young

Washington. He first gained public notice when, as adjutant of one of Virginia's four

military districts, he was dispatched (October 1753) by Gov. Robert Dinwiddie on a

fruitless mission to warn the French commander at Fort Le Boeuf against further

encroachment on territory claimed by Britain. Washington's diary account of the dangers

and difficulties of his journey, published at Williamsburg on his return, may have helped

win him his ensuing promotion to lieutenant colonel. Although only 22 years of age and

lacking experience, he learned quickly, meeting the problems of recruitment, supply, and

desertions with a combination of brashness and native ability that earned him the respect

of his superiors.

|

| |

| French and Indian War. |

| |

|

In April 1754, on his way to

establish a post at the Forks of the Ohio (the current site of Pittsburgh), Washington

learned that the French had already erected a fort there. Warned that the French were

advancing, he quickly threw up fortifications at Great Meadows, Pa., aptly naming the

entrenchment Fort Necessity, and marched to intercept advancing French troops. In the

resulting skirmish the French commander the sieur de Jumonville was killed and most of his

men were captured. Washington pulled his small force back into Fort Necessity where he was

overwhelmed (July 3) by the French in an all-day battle fought in a drenching rain.

Surrounded by enemy troops, with his food supply almost exhausted and his dampened

ammunition useless, Washington capitulated. Under the terms of the surrender signed that

day, he was permitted to march his troops back to Williamsburg.

|

| |

|

Discouraged by his defeat and

angered by discrimination between British and colonial officers in rank and pay, he

resigned his commission near the end of 1754. The next year, however, he volunteered to

join British general Edward Braddock's expedition against the French. When Braddock was

ambushed by the French and their Indian allies on the Monongahela River, Washington,

although seriously ill, tried to rally the Virginia troops. Whatever public criticism

attended the debacle, Washington's own military reputation was enhanced, and in 1755, at

the age of 23, he was promoted to colonel and appointed commander in chief of the Virginia

militia, with responsibility for defending the frontier. In 1758 he took an active part in

Gen. John Forbes's successful campaign against Fort Duquesne. From his correspondence

during these years, Washington can be seen evolving from a brash, vain, and opinionated

young officer, impatient with restraints and given to writing admonitory letters to his

superiors, to a mature soldier with a grasp of administration and a firm understanding of

how to deal effectively with civil authority.

|

| |

| Virginia Politician. |

| |

|

Assured that the Virginia

frontier was safe from French attack, Washington left the army in 1758 and returned to

Mount Vernon, directing his attention toward restoring his neglected estate. He erected

new buildings, refurnished the house, and experimented with new crops. With the support of

an ever-growing circle of influential friends, he entered politics, serving (1759-74) in

Virginia's House of Burgesses. In January 1759 he married Martha Dandridge Custis, a

wealthy and attractive young widow with two small children. It was to be a happy and

satisfying marriage. After 1769, Washington became a leader in Virginia's opposition to

Great Britain's colonial policies. At first he hoped for reconciliation with Britain,

although some British policies had touched him personally. Discrimination against colonial

military officers had rankled deeply, and British land policies and restrictions on

western expansion after 1763 had seriously hindered his plans for western land

speculation. In addition, he shared the usual planter's dilemma in being continually in

debt to his London agents. As a delegate (1774-75) to the First and Second Continental

Congress, Washington did not participate actively in the deliberations, but his presence

was undoubtedly a stabilizing influence. In June 1775 he was Congress's unanimous choice

as commander in chief of the Continental forces.

|

| |

| American Revolution. |

| |

|

Washington took command of the

troops surrounding British-occupied Boston on July 3, devoting the next few months to

training the undisciplined 14,000-man army and trying to secure urgently needed powder and

other supplies. Early in March 1776, using cannon brought down from Ticonderoga by Henry

Knox, Washington occupied Dorchester Heights, effectively commanding the city and forcing

the British to evacuate on March 17. He then moved to defend New York City against the

combined land and sea forces of Sir William Howe. In New York he committed a military

blunder by occupying an untenable position in Brooklyn, although he saved his army by

skillfully retreating from Manhattan into Westchester County and through New Jersey into

Pennsylvania. In the last months of 1776, desperately short of men and supplies,

Washington almost despaired. He had lost New York City to the British; enlistment was

almost up for a number of the troops, and others were deserting in droves; civilian morale

was falling rapidly; and Congress, faced with the possibility of a British attack on

Philadelphia, had withdrawn from the city.

|

| |

|

Colonial morale was briefly

revived by the capture of Trenton, N.J., a brilliantly conceived attack in which

Washington crossed the Delaware River on Christmas night 1776 and surprised the

predominantly Hessian garrison. Advancing to Princeton, N.J., he routed the British there

on Jan. 3, 1777, but in September and October 1777 he suffered serious reverses in

Pennsylvania--at Brandywine and Germantown. The major success of that year--the defeat

(October 1777) of the British at Saratoga, N.Y.--had belonged not to Washington but to

Benedict Arnold and Horatio Gates. The contrast between Washington's record and Gates's

brilliant victory was one factor that led to the so-called Conway Cabal--an intrigue by

some members of Congress and army officers to replace Washington with a more successful

commander, probably Gates. Washington acted quickly, and the plan eventually collapsed due

to lack of public support as well as to Washington's overall superiority to his rivals.

After holding his bedraggled and dispirited army together during the difficult winter at

Valley Forge, Washington learned that France had recognized American independence. With

the aid of the Prussian Baron von Steuben and the French marquis de LaFayette, he

concentrated on turning the army into a viable fighting force, and by spring he was ready

to take the field again. In June 1778 he attacked the British near Monmouth Courthouse,

N.J., on their withdrawal from Philadelphia to New York. Although American general Charles

Lee's lack of enterprise ruined Washington's plan to strike a major blow at Sir Henry

Clinton's army at Monmouth, the commander in chief's quick action on the field prevented

an American defeat.

|

| |

|

In 1780 the main theater of the

war shifted to the south. Although the campaigns in Virginia and the Carolinas were

conducted by other generals, including Nathanael Greene and Daniel Morgan, Washington was

still responsible for the overall direction of the war. After the arrival of the French

army in 1780 he concentrated on coordinating allied efforts and in 1781 launched, in

cooperation with the comte de Rochambeau and the comte d'Estaing, the brilliantly planned

and executed Yorktown Campaign against Charles Cornwallis, securing (Oct. 19, 1781) the

American victory.

|

| |

|

Washington had grown enormously

in stature during the war. A man of unquestioned integrity, he began by accepting the

advice of more experienced officers such as Gates and Charles Lee, but he quickly learned

to trust his own judgment. He sometimes railed at Congress for its failure to supply

troops and for the bungling fiscal measures that frustrated his efforts to secure adequate

materiel. Gradually, however, he developed what was perhaps his greatest strength in a

society suspicious of the military--his ability to deal effectively with civil authority.

Whatever his private opinions, his relations with Congress and with the state governments

were exemplary--despite the fact that his wartime powers sometimes amounted to dictatorial

authority. On the battlefield Washington relied on a policy of trial and error, eventually

becoming a master of improvisation. Often accused of being overly cautious, he could be

bold when success seemed possible. He learned to use the short-term militia skillfully and

to combine green troops with veterans to produce an efficient fighting force.

|

| |

|

After the war Washington returned

to Mount Vernon, which had declined in his absence. Although he became president of the

Society of the Cincinnati, an organization of former Revolutionary War officers, he

avoided involvement in Virginia politics. Preferring to concentrate on restoring Mount

Vernon, he added a greenhouse, a mill, an icehouse, and new land to the estate. He

experimented with crop rotation, bred hunting dogs and horses, investigated the

development of Potomac River navigation, undertook various commercial ventures, and

traveled (1784) west to examine his land holdings near the Ohio River. His diary notes a

steady stream of visitors, native and foreign; Mount Vernon, like its owner, had already

become a national institution.

|

| |

|

In May 1787, Washington headed

the Virginia delegation to the Constitutional Convension in Philadelphia and was

unanimously elected presiding officer. His presence lent prestige to the proceedings, and

although he made few direct contributions, he generally supported the advocates of a

strong central government. After the new Constitution was submitted to the states for

ratification and became legally operative, he was unanimously elected president (1789).

|

| |

| The Presidency |

| |

|

Taking office (Apr. 30, 1789) in

New York City, Washington acted carefully and deliberately, aware of the need to build an

executive structure that could accommodate future presidents. Hoping to prevent

sectionalism from dividing the new nation, he toured the New England states (1789) and the

South (1791). An able administrator, he nevertheless failed to heal the widening breach

between factions led by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury

Alexander Hamilton. Because he supported many of Hamilton's controversial fiscal

policies--the assumption of state debts, the Bank of the United States, and the excise

tax--Washington became the target of attacks by Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans.

|

| |

|

Washington was reelected

president in 1792, and the following year the most divisive crisis arising out of the

personal and political conflicts within his cabinet occurred--over the issue of American

neutrality during the war between England and France. Washington, whose policy of

neutrality angered the pro-French Jeffersonians, was horrified by the excesses of the

French Revolution and enraged by the tactics of Edmond Genet, the French minister in the

United States, which amounted to foreign interference in American politics. Further, with

an eye toward developing closer commercial ties with the British, the president agreed

with the Hamiltonians on the need for peace with Great Britain. His acceptance of the 1794

Jay's Treaty, which settled outstanding differences between the United States and Britain

but which Democratic-Republicans viewed as an abject surrender to British demands, revived

vituperation against the president, as did his vigorous upholding of the excise law during

the WHISKEY REBELLION in western Pennsylvania.

|

| |

| Retirement and Assessment |

| |

|

By March 1797, when Washington

left office, the country's financial system was well established; the Indian threat east

of the Mississippi had been largely eliminated; and Jay's Treaty and Pinckney's Treaty

(1795) with Spain had enlarged U.S. territory and removed serious diplomatic difficulties.

In spite of the animosities and conflicting opinions between Democratic-Republicans and

members of the Hamiltonian Federalist party, the two groups were at least united in

acceptance of the new federal government. Washington refused to run for a third term and,

after a masterly Farewell Address in which he warned the United States against permanent

alliances abroad, he went home to Mount Vernon. He was succeeded by his vice-president,

Federalist John Adams.

|

| |

|

Although Washington reluctantly

accepted command of the army in 1798 when war with France seemed imminent, he did not

assume an active role. He preferred to spend his last years in happy retirement at Mount

Vernon. In mid-December, Washington contracted what was probably quinsy or acute

laryngitis; he declined rapidly and died at his estate on Dec. 14, 1799.

|

| |

| |

| |

| |